In Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, a rogue American general hijacks a US airforce base and orders a squadron of B-52 bombers armed with hydrogen bombs to strike deep inside the USSR. As the President of the United States gathers his generals and cabinet at the War Room in the Pentagon, it becomes obvious that some of the bombers are uncontactable and that a nuclear strike on the Soviets is inevitable.

In a desperate bid to somehow prevent the situation from escalating into a global nuclear conflict, the President summons the Soviet ambassador and informs him of the attack, offering him the flight trajectories, targets, and the entire US war plan to help the Soviets to shoot down the bombers. It is for naught, however: the ambassador tells the Americans that the Soviets have devised a secret Doomsday Machine. If the USSR were ever to become the target of a nuclear attack, a string of hidden underground hydrogen bombs would detonate, rendering the entire earth uninhabitable.

It is at this point that the President’s scientific adviser and architect of the US nuclear programme, the wheelchair-bound former Nazi scientist Dr. Strangelove (“Merkwürdigliebe” before his naturalisation), pipes up: “The whole point of the Doomsday Machine is lost,” he says, “if you keep it a secret. Why didn’t you tell the world, eh!?” “It was to be announced at the at Party Congress on Monday,” replies the ambassador. “As you know, the Premier loves surprises.”

The scene perfectly captures the contradictions inherent in the logic of deterrence via mutually assured destruction. For deterrence to work, you must signal both genuine capacity and real intent to mortally wound your adversary. At the same time, you must never actually make your opponent think are actively planning to use that capacity, as this would ensure your own destruction.

There is good reason to believe that Iran did not intend to the strike to be an opening salvo in an all-out conflict, and that the attack was meant to be a message, if an extreme one at that. Before the attack, Tehran engaged in active back-channel communications with the US and it’s regional allies to reassure them that it did not seek to ignite a war.

For decades now, Israel and Iran have been locked in a tit-for-tat shadow conflict, with both sides seeking to credibly threaten the other without igniting a full-blown regional war. When on 13 April Iran, in response to an Israeli airstrike on an Iranian consulate (and thus Iran’s sovereign soil) in Damascus, launched more than 300 drones and missiles towards Israel, this conflict reached an unprecedented fever-pitch and risked drawing the entire region into an open and full-blown war.

Israeli anti-missile systems intercept Iranian drones and missiles, Israel April 14, 2024. REUTERS/Amir Cohen

While deterrence and mutually assured destruction between two nuclear states with clear red lines is relatively straightforward, how does deterrence work between two states that have been engaged in low-level conflict for decades without establishing clear red lines with each other? And with regional and global tensions at a height not seen since the Cold War, how long can they last before someone loses their nerve and the Doomsday Machine is triggered?

Israel, Iran, and the US: a web of direct and indirect deterrence

In the Israeli-Iranian conflict, Israel is the stronger party by a wide margin. Israel is in possession of around 80 nuclear warheads (the existence of which it refuses to acknowledge). Iran has zero. Most importantly, Israel enjoys an extremely close alliance with the world’s only global superpower, the United States, and is supported by both of the US’ two political parties. The US, which has its own historical enmity with Iran, is capable of swiftly destroying the Iranian armed forces and national infrastructure by conventional means alone. It is doubtful, especially after April 13, that Iran is capable of doing so to Israel, let alone while facing a US-led regional coalition.

“Iran, conscious that it is the weaker party in this conflict, is far more concerned with signalling its capacity for deterrence to the US and Israel than vice versa. This has led the regime’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to cultivate what it calls strategic depth – the ability to deter the US by threatening its close allies, namely Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.“

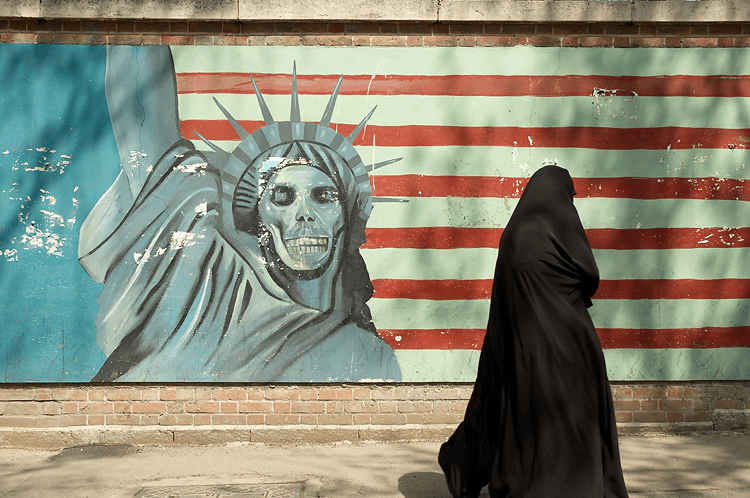

Iran, conscious that it is the weaker party in this conflict, is far more concerned with signalling its capacity for deterrence to the US and Israel than vice versa: the latter two have nothing to prove, as its strength is obvious. Iran’s approach to building deterrence against Israel has thus been strategic: the Islamic Republic’s leaders are well aware that Israel’s military superiority depends on US support. In fact, the US is Iran’s primary adversary – after all, the US is the neo-colonial overlord that Supreme Leader Khamenei, President Ebrahim Raisi, and their fellow revolutionaries overthrew alongside Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The US has sought to undermine the regime in Tehran ever since it overthrew its staunch ally the Shah and after the 1979-80 US embassy hostage crisis.

Anti-US graffiti on the walls of the former US embassy in Tehran. In Iran, the US is remembered for organising a coup against democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, and replacing him with the autocratic Shah who was later ousted. Wikimedia Commons.

Iran, however is incapable of seriously threatening the US. This, alongside genuine ideological belief in exporting the revolution and animosity against Israel, has led the regime’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC, known in Persian as Sepah, the section of the Iranian armed forces tasked with defending the Islamic Revolution rather than the nation’s borders) to cultivate what it calls strategic depth – the ability to deter the US by threatening its close allies, namely Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. The IRGC has achieved this by forming strong relationships with regional actors that share its goals and often ideology. The most prominent ones are Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and Hamas in Gaza.1

“Israel’s approach to deterrence vis-a-vis Iran has been tactical and operational rather than to strategic, as strategically it can rely on the US to do the heavy lifting to contain and ‘manage’ Iran. Israel foreign intelligence agency, the Mossad, regularly conducts targeted assassinations and kidnappings of Iranian nuclear scientists, conducts cyberattacks, and opportunistically assassinates IRGC leaders in Syria.“

Israel’s approach to deterrence vis-a-vis Iran has been tactical and operational rather than to strategic, as strategically it can rely on the US to do the heavy lifting in mustering US and regional forces to contain and ‘manage’ Iran. Israel’s foreign intelligence agency, the Mossad, regularly conducts targetted assasinations and kidnappings of Hamas members abroad, as in Tunisia in 2017 and Malaysia in 2022 to name a few high-profile examples.

The Israelis conduct similar operations against Iran, assassinating key members of Iran’s nuclear programme and conducting cyber attacks on Iran’s strategic infrastructure. Israel also conducts regular airstrikes in Syria, where it targets IRGC logistics hubs and networks that the Islamic Republic uses to supply arms to Hezbollah and Hamas, which in turn use these weapons to target Israel.

The background to April 13

Ever since Hamas’ October 7 massacre of Israeli civilians, Israel has doubled down on these efforts to cut off Iranian support for Hezbollah. Israel has a long history of violating Lebanese airspace, but this campaign reached a new height when in January this year Israel assassinated Hamas deputy leader Saleh al-Arouri by conducting a strike in the Dahiyeh suburb of Beirut.

“Arouri’s killing was part of a continuum of similar tactical attacks against Iran and its allied factions, including the strike on IRGC commander Sayyed Reza Moussavi, also killed at his residence in Damascus, in December. On January 4, a US drone strike killed a IRGC-backed militia leader in Baghdad.“

The attack sent shockwaves across Lebanon, which has been going through one of the worst economic crises in the world. Ordinary Lebanese feared that the attack might reignite sectarian tensions between Hezbollah and the country’s other religious and political groups, as the country still grapples with the trauma of its 1975-90 civil war and Israel’s 1982 invasion.2

Firefighters clear the wreckage of Israel’s strike on Hamas leader Saleh al-Arouri Dahiyeh, Beirut. Marwan Tahtah/Getty Images.

Arouri’s killing was part of a continuum of similar tactical attacks against Iran and its allied factions, including the strike on IRGC commander Sayyed Reza Moussavi, also killed at his residence in Damascus in December. On January 4, a US drone strike killed a IRGC-backed militia leader in Baghdad.

What ultimately triggered Iran’s launch of a combined drone and missile-strike on Israel was when on 1. April Israel conducted a drone strike against an Iranian consulate in Damascus, killing two IRGC generals. This was not an attack on a private residence – it was an attack on what is under international law Iranian sovereign soil. US sources indicate that Israel informed them of the strike only at the last minute, and thought of it simply as business as usual. According to the New York Times:

“The Israelis had badly miscalculated, thinking that Iran would not react strongly, according to multiple American officials who were involved in high-level discussions after the attack, a view shared by a senior Israeli official.”

The April 13 attack: deterrent signal or full-blown offensive?

There is good reason to believe that Iran did not intend to the strike to be an opening salvo in an all-out conflict, and that the attack was meant to be a message, if an extreme one at that.

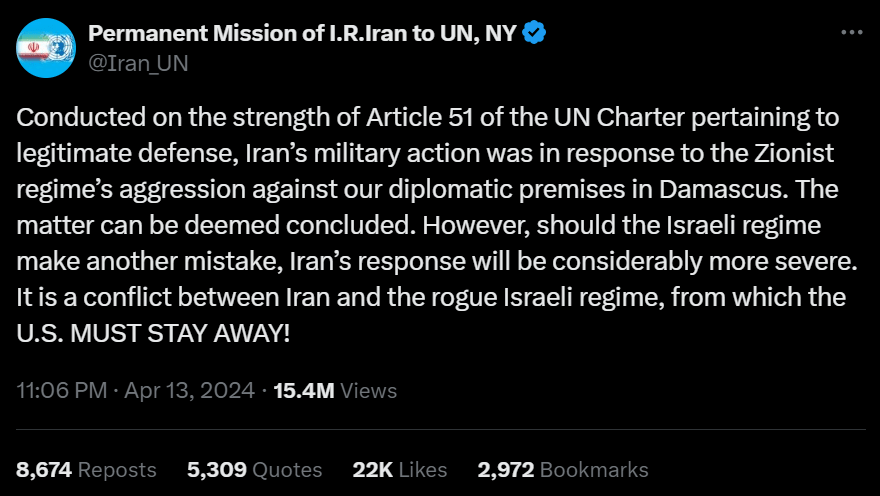

Before the attack, Tehran engaged in active back-channel communications with the US and it’s regional allies to reassure them that it did not seek to ignite a war: on April 11 Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian signalled to the US, via Oman, that it did not seek to trigger a war. Amirabdollahian also stated that he gave US regional allies, identified as the Gulf monarchies in most reports, 72 hours’ prior notice of the attack. Once the strikes had concluded, the Iranian mission to the UN tweeted that “The matter can be deemed concluded.”

Tweet posted by the Iranian Embassy to the UN announcing Iran’s retaliation to be ‘concluded’. Note how the tweet singles out the US as the greater threat to Iran.

This is what we can glean from direct communications from Iranian the leadership. Other factors support this: out of it’s arsenal of 3,000 ballistic missiles (which form the spearhead of combined missile-drone assault, drones drawing in missiles defences), Iran fired around 100. During Iran’s assault Hezbollah, based in Southern Lebanon, fired only a few dozen missiles at Israeli barracks in the occupied Golan Heights, compared to its arsenal of thousands of missiles which could have been launched to overwhelm Israeli defences. Missile and drone support from the Houthis in Yemen was limited. As Dr Sanam Vakil and Bilal Y. Saab from Chatham House put it:

“Had Iran’s intent been to hurt Israel, it wouldn’t have violated a core principle of military operations – the element of surprise. But it did… Indeed, had Iran sought to inflict serious pain on Israel, it would have incorporated a heavier dose of fast-flying and precision-guided ballistic missiles, giving Israel very little time to prepare and respond.”

As a result of this telegraphing, Israeli and allied air defences were fortunately able to shoot down 99% of incoming targets. The results of the Islamic Republic’s unprecedented assault were minor damage to an airbase in the Negev, and in a deep twist of irony the serious injury of a 7-year old Arab girl from the local Beduin community.

Deterrence without nukes: a Strangelovian pattern

Militarily, Iran’s assault could be deemed a failure. But under the Strangelovian logic of deterrence, the attack achieved what it set out to accomplish: to signal capacity and to signal intent, while inflicting too little damage to warrant the risk of a genuinely destructive confrontation. The assault fits a past pattern of the Islamic Republic looking to save face after serious blows from it’s militarily superior adversaries – namely the US – by warning them of an impending retaliatory strike, giving its enemies time to evacuate targets while allowing the regime a chance to make a tactically empty show of force.

Qasem Soleimani, former leader of the IRGC’s crack Quds Force. Mohammed Saeed Saeedi/Fars Media Corporation.

This same choreography played out in January 2020 after US forces under Donald Trump killed the Revolutionary Guard leader Qasem Soleimani with a drone strike near Baghdad airport. As with the Israeli strike on the embassy compound in Damascus, Iran deemed the attack a violation of the norms of the US-Iranian conflict (later, it was confirmed to be in violation of international law). In response, Iran attacked US military bases in Iraq – but secretly warned the US military of the strikes ahead of time to prevent genuine escalation.

“The US has regularly warned Russia of missile strikes it is about to conduct in Syria to prevent casualties of Russian soldiers embedded with Bashar al-Assad’s forces. Even Iran’s nuclear programme follows the same, Strangelovian logic of these attacks-as-shows-of-force.“

This is in fact common conflicting parties in the region: the US itself has regularly warned Russia of missile strikes it is about to conduct in Syria to prevent casualties of Russian soldiers embedded with Bashar al-Assad’s forces. Even Iran’s nuclear programme follows the same, Strangelovian logic of these attacks-as-shows-of-force. Ever since Trump withdrew from the JCPOA (‘Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action,’ better known to the public as ‘Obama’s nuclear deal’) in May 2018, Iran has sought to maintain a realistic capacity to develop a nuclear warhead in about a year to half a year. If Iran gets too close to actually obtaining one, it risks serious military action from Israel and/or the US. If it does not maintain the capacity to realistically develop one, it loses an important bargaining chip and deterrent.

A message to the US’ Arab allies

In the past, Iran has used its strategic depth and links with Hezbollah, the Houthis, and Hamas to pressure not only Israel, but also the US’ and Israel’s Arab allies, namely the Gulf monarchies, to great to great effect. It is likely that April 13 was a message to them as much as it was for Israel to press the US to de-escalate.

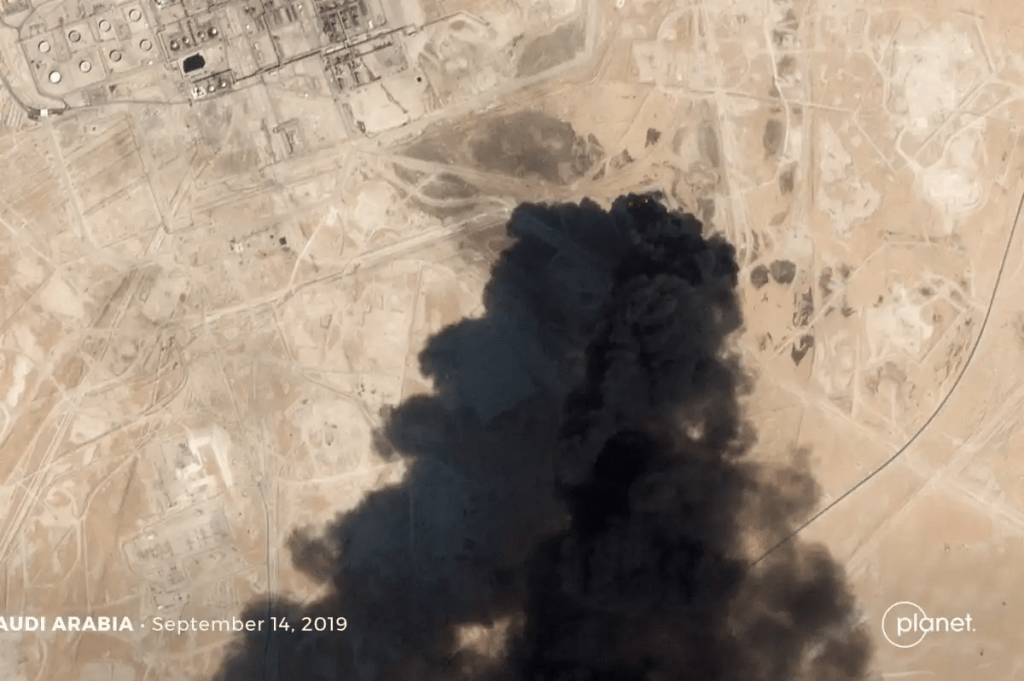

Saudi Aramco facility in Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia after Houthi drone strikes set fire to Saudi oil facilities. Captured by a Planet Dove satellite on September 14, 2019. Planet/Twitter

From the 2011 Arab Spring until the Saudi-Iran peace deal in 2023, Iran was engaged in a shadow conflict with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and when regional tensions ramp up, the IRGC tends to increase activity against these two key US allies. In 2019, during Trump’s ‘Maximum Pressure’ campaign against Iran that included withdrawal from the JCPOA, new sanctions, and the designation of the IRGC as a terrorist organisation, the Houthis launched drone attacks on Saudi oil sites with Iranian support, temporarily halting 5% of global oil production. Around the same time, Iranian naval mines placed off the coast of Fujairah in the UAE hit an oil tanker. Both of these attacks yielded Iran de-escalation in UAE and Saudi lobbying against Iran in Washington as Abu Dhabi and Riyadh urged more caution, at least temporarily.

“It appears that Iran’s leaders are seeking a repeat of this strategy: before the April 13 attacks, the IRGC warned the UAE (which has normalised relations with Israel) that it deemed Israeli presence in the UAE ‘a threat’.”

It appears that Iran’s leaders are seeking a repeat of this strategy: before the April 13 attacks, the IRGC warned the UAE (which has normalised relations with Israel) that it deemed Israeli presence in the UAE ‘a threat’. The fact that Iran warned these states (and by proxy, the US and Israel) of its attack in advance shows that it does not seek directly threaten the Gulf states. But the experience of Iranian missiles flying over or close to their airspace has unnerved them, and has pushed Gulf governments, Iraq, and Jordan to call on the US lean on Israel to de-escalate. According to a Reuters’ source close to Gulf governments:

“Nobody wants an escalation. Everybody wants to contain the situation… The pressure is not on Iran alone. The pressure is now on Israel not to retaliate… [any Israeli retaliation] will affect all the region”.

It is likely that the April 13 strike was meant as signal to the US’ Arab allies as much as it was to Israel and the US itself.

The Israeli calculus

Ever since Hamas’ October 7 massacre of Israeli civilians, Israeli policymakers and public have been living through a state of arrested trauma. Attack has pushed the already increasingly right-wing government to give up all pretence of following international law or norms when it comes to dealing with the Palestinians as a whole and Hamas and its backers specifically. The fact that Israeli leaders did not think attacking an Iranian embassy compound, itself echoing Trump’s unprecedented assassination of Soleimani in 2020, would be seen as an escalation by Iran, is telling of Israel’s single-minded focus on short-term operational gains.

Palestinians inspect the ruins of Aklouk Tower destroyed in Israeli airstrikes in Gaza City on October 8, 2023. Palestinian News & Information Agency/Wikimedia Commons.

Yagil Levy, a professor of military sociology at the Open University of Israel, described the Israeli decision-making process thusly to The Guardian:

“Israel is led by the availability of its weapons systems. And whenever the country or the leadership feels that they have a good intelligence, a good opportunity and available weaponry systems that can do the job, Israel strikes… Israel doesn’t have a really strategic approach … the attempt to identify the [connections] between specific military actions and expected benefits is not in the repertoire of the Israeli leadership.”

This opportunism fits the description of Israeli operations against Iran outlined at the beginning of the blog: they are tactical and operational, rather than strategic. Israel has sophisticated military intelligence and striking capabilities, and it uses them as it sees fit to weaken its enemies, without consider the longer-term strategic effects these will have on its adversaries’ posture. There is no incentive to do so, as Israel’s short, medium, and long-term strategy boils down to unconditional US support and backing for its positions in the region.

Israel’s strike on the Islamic Republic’s embassy complex in Damascus on 1 April. Rajanews/Wikimedia Commons.

Israel’s retaliatory strike against on April 19: Iran follows exactly the same pattern as its strikes against Iran and Iranian targets beforehand: swift and unannounced. International pressure on Israel to contain escalation clearly paid off, as Israel only targeted minor military targets near Isfahan, and did not target any of Iran’s nuclear facilities (also located in Isfahan). Apparently, Israel’s original plan was to strike major military targets near Tehran, Iran’s capital.

“On the face of it, both sides can now claim victory: Iran has demonstrated that if backed into a corner it has the willingness and capability to launch direct attacks on US allies. Israel, in turn, has demonstrated that it can easily take out air defences protecting Iranian nuclear sites.”

On the face of it, both sides can now claim victory: Iran has demonstrated that if backed into a corner it has the willingness and capability to launch direct attacks on US allies. Israel, in turn, has demonstrated that it can easily take out air defences protecting Iranian nuclear sites. But the audience for Israel’s military action is as much domestic as international, and its likely that for hardliners in the Israeli public the strikes might not be perceived to be sufficient as deterrence or retaliation. Immediately after the Israeli strikes, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir casually tweeted a single word: “lame!”

“Scarecrow!” slang in Modern Hebrew for English ‘lame’.

Ultimately, Israel stands to gain the most from the recent escalation in tensions. The Gulf monarchs, while publicly critical of Israeli crimes in Palestine, are privately in favour of closer ties with Israel and the US. In the short term Iran might have successfully got them to pressure Israel, but in the long run the attack will likely draw them closer together. US and Western public sympathy for Israel, dented by months-long images of dead Palestinian civilians, ruined cities, and news of war crimes and crimes against civilians, has temporarily been buoyed, allowing Israel more leeway in escalation both in Gaza and the broader region.

Conclusions: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

In the game of deterrence and signalling between Iran and Israel, it looks like Iran is the only one playing. Only time will fully tell, but the nature of Israel’s retaliatory strikes shows that it is not inclined to give back-channel warnings to Iran or signpost its military actions any more intentionally than it did before. Nor is Israel looking to de-escalate in Gaza: after displacing 1.7 million Gazans (out of a 2 million total) by bombing Gaza city and Khan Younis to rubble, Israel is pushing on with its planned offensive in Rafah, where a million of the Palestinians it has displaced are now seeking shelter.

“In Dr. Strangelove, nuclear war and global annihilation is brought on by a combination of rogue actors and the Soviets fundamentally misunderstanding how deterrence works. But between Israel and Iran, there seems to be little Israeli willingness to even acknowledge that signals are being sent.”

Iran, in turn, is facing an emboldened and more aggressive Israel combined with a reinforced US military presence and attention abroad. At home, the Islamic Republic continues to be abysmally unpopular due widespread corruption and the suppression of basic civil liberties. After April 13 and heightened tensions with Israel, the Morality Police returned to the streets, and the state has doubled down on reinforcing the mandatory wearing of the headscarf.

People participating in the Zan, Zendegi, Azadi protests in Iran in Tehran, September 2022. The protests were triggered after 22 year old Mahsa Amini was beaten to death by the Morality Police for ‘failing to wear the hijab properly.’ Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in outrage, with an estimated 20,000 arrested and 500 killed by security forces.

Men and women associated with the Zan, Zendegi, Azadi protests (“Women, Life, Freedom”) have been arrested; those already arrested are receiveing harsher sentences. Yesterday, Isfahan’s Revolutionary Court sentenced Rapper Toomaj Salehi to death for supporting the Zan, Zendegi, Azadi protests under the Article 284 of the Penal Code for ‘spreading corruption on earth’, an article falls drastically short of international legal standards for its outrageous vagueness and arbitrariness. As emboldened as Israel feels be on the regional stage, the Islamic Republic feels besieged both at home and abroad.

“Ultimately, Israel stands to gain the most from the recent escalation in tensions. The Gulf monarchs, while publicly critical of Israeli crimes in Palestine, are privately in favour of closer ties with Israel and the US. In the short term Iran might have successfully got them to pressure Israel, but in the long run the attack will likely draw them closer together.”

In Dr. Strangelove, nuclear war and global annihilation is brought on by the combination of a rogue American general and the Soviets fundamentally misunderstanding how deterrence works. In Dr. Strangelove’s words, “The whole point of the Doomsday Machine is lost if you keep it a secret.” But between Israel and Iran, there seems to be little Israeli willingness to even acknowledge that signals are being sent – that burden is left to Iran and the Americans, who are negotiating their own fraught relationship. Clear red lines, and direct back-channel talks between Israel and Iran must be established in order to prevent another April 13 or, God forbid, a full-blown war from being triggered.

Dr. Strangelove ends with Major Kong, the Texan commander of a nuclear B-52 Bomber and a true believer in the righteousness of America’s cause, unjamming a stuck hydrogen bomb by jumping on it. As he rides the bomb down to its target, screaming ‘yeehaw’ and waving his Stetson, he is unaware that his lone crusade is not even a miscalculation: it is an accident, pure and simple. While tomorrow’s Kong might not wear a Stetson, we better hope he thinks twice before leaping into something he does not understand.

- Dubbed the ‘Axis of Resistance’, these geographically and ideologically diverse groups are often lumped together as ‘Iranian proxies,’ and there is a knee-jerk tendency to think of all of them as under direct Iranian control, rather than having their own agendas and interests. While Iran certainly exerts a lot of control over Hezbollah and many Iraqi militias, its influence over the Houthis and Hamas beyond the role of material and moral patron and ally of convenience is doubtful. In the immediate aftermath of Hamas’ slaughter of Israeli civilians on October 7, many op-eds squarely laid the blame at Iran’s door. Later intelligence and analysis rescinded this view. ↩︎

- Ironically enough, Lebanon’s Shia Muslims were politically and militarily marginalised until Israel’s 1982 invasion, which saw heavy fighting in Lebanon’s mostly Shia south. It was the resistance to that invasion that gave birth to Hezbollah as an organisation and saw them rise to a position of power inside Lebanon. ↩︎

Leave a comment